This was originally a twitter thread

I’m seeing a lot of people talking about how people should go into HS only jobs or trades instead of university. Lets put aside that the unemployment rate for trades is often worse than jobs that require a university degree, instead I’ll tell you a story about the economy.

I grew up in BC. And the alternative to university that was pushed when I was in high school was either the family farm (I lived in a farming community) or the lumber industry. FYI, this is a #CareerDevelopment story.

It was the 90s and the lumber industry was strong. If you weren’t from a farming family the non-university jobs talked about were forestry/lumber, construction, plumber/electrician, and first responders. In the mill towns it was pretty much just forestry/lumber.

The forestry and lumber industry was very people intensive. People to cut trees, people to plant trees, people to move logs, people to run the mills, people to support all of those industries, people to work in secondary industries (wood product manufacturing).

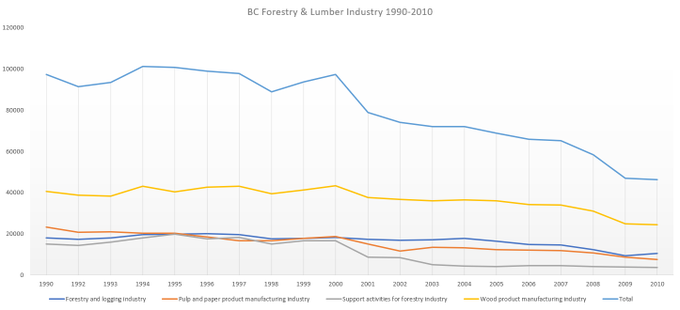

So it’s the 90s and there’s about 100,000 jobs in the industry. They’re good jobs, well paid jobs. Most of them require no post-secondary or maybe a certificate.

When I moved to Calgary five years ago the way people talked about the oil sands was exactly the way people talked about the lumber industry in BC when I was a kid.

Now, I say that there were good jobs, and there were, but the number of jobs wasn’t really going up. And this doesn’t get noticed in the short term, but what it means is that the industry isn’t growing, which means the future won’t be bright for people trying to get in.

Oh, productivity kept going up, the money the industry brought into the province kept going up, but employment was stagnant. That was never mentioned to teens looking to what their future could be though.

So, what happened to that industry? Well, the 2000s happened. And at the end of it the industry had shrunk 50%. The 2000s were filled with talk about how we needed to “retrain” forestry and lumber workers.

Magic bullet after magic bullet was proposed. The government started talking up trades, while ignoring the increasing trades unemployment rate. The jobs that had lower unemployment? Work that required a bachelors degree.

FYI, here’s the Forestry & Lumber industry over 20 years. Yeah, it was bad.

I talked in depth about the so-called Trades shortages about five years ago. TL:DR the only trades that have lower unemployment than bachelors degree requiring jobs are the ones that required two years of post-secondary apprenticeship program.

That’s an important point a lot of people forget. Trades school in Canada is run through the same post-secondary system as Bachelors. The programs are generally 1/2 the length, but that’s it. So when I talk about post-secondary I mean Certs, Diplomas, Trades, and Degrees.

What’s the point of this story?

- jobs that don’t require post-secondary are being automated

- once a resource extraction industry automates they never bring the jobs back

- people with post-secondary have an easier time changing industries when jobs disappear

So, if you want to tell someone not to go to get a Bachelors degree, you’re still probably going to be telling them to go to post-secondary. That’s the way of the world now.

As I look back on the people who talked up forestry when I was a kid I notice something. Most of them were let go when the mill automated or they changed industries in their late 40s. Some of them went to post-secondary then to retrain/reskill, and that’s a good thing.

But here’s where it comes to Alberta. The same automation warning signs are there for the oil & gas industry. I had a student who I worked with a few years ago. He’d spent 15 years in the oil sands and decided to change jobs. Why? Because he saw the signs. He knew that his job was going to be automated in the next five years, so he decided to train now for the IT job that was going to replace 10 people who were doing what he was doing before.

And that’s where we get back to #CareerDevelopment. Students need to learn not what the past industries were, but what industries are growing and flourishing. That is going to require post-secondary, of some kind.