Originally two twitter threads: thread 1 thread 2.

It took everyone a bit of time to notice this year, but the labour market shortage is basically being driven by mass retirements over the last two years, just not where you think (is the cultural moment for a Madisynn MCU reference past? Probably). Employment stats time. All of this is some back of the napkin calculations from Stats Can’s info on people accessing retirement benefits and leaving or entering the workforce.

We know people have been pushing retirements a bit later, and recent stats back this up. In the last 9 years, as this has been happening there’s been an average of about 100K new retirees under 65 in Canada. It took a dive during the pandemic of 8% and 10%. So more people retiring a year or two or five later than they used to. As with every other economic shock, the pandemic made more people avoid early retirement a little. So fewer people retiring under 65.

What you might not know though is that the number of people retiring at 65 went up during the pandemic, up 5.4% for men and 6.6% for women. Interesting, yes? So during the pandemic fewer people retired early, but more retired at the standard age.

But we also have stats for those who stayed in the workforce well past standard retirement age. For those still working at 70 or above the retirement numbers during the pandemic jumped over 300% for men and over 900% for women. It’s not quite as drastic for the 66-69 group, but it’s still significantly increased. So all those people who delayed retirement before the pandemic decided this was the right time to retire.

The question everyone was asking as this labour market tightening happened was: where are the workers? Well the people who were working well past retirement age have now retired. And that might not seem like a lot, but it’s about an extra 100 thousand people (over 65) leaving the workforce over the last last two years than was expected, and that’s not counting the over 5,000 people in the 20-65 age group who died in Canada from COVID.

So the Baby Boomers are retiring, as was foretold. We expected this. But, even more impactful, the incoming age cohorts are shrinking, the current group of teens is 20% smaller than the current group of new professionals. The preparing for retirement cohort is the same size as the new professionals cohort, so the labour shortage isn’t going to go away any time soon, because the group of replacement workers coming up isn’t big enough to make an impact.

What does this mean for retention then? Employers need to adapt, because young people have something they haven’t had since before 2006: options.

What was a shortage in manufacturing, construction, and retail in 2018 has now hit health care and professional roles, and it will just keep going. I’ve been thinking a lot about this with the discussion regarding work-from-home, return-to-work, quiet quitting / work to rule, skills gaps, and the labour shortage.

If you want your employees to go above and beyond you need to offer one of these things:

- intrinsic rewards: motivates staff to want to do more, like work that is impactful or fulfilling or helps them grow and develop in the ways they want to.

- extrinsic rewards: pay for the extra time and effort either through overtime, bonuses, or other tangible rewards.

- career development: people will do more for you if their positions are secure or if they have a path to promotion.

Once upon a time these three were considered standard in a professional role, but over time as the number of professional roles have grown, they’ve decreased. That probably was because of labour oversupply. Retirement age got later and more people finished university so the total # of people wanting professional jobs went up much faster than the number of jobs. But that started shifting about 4 years ago, and rapidly in the last year.

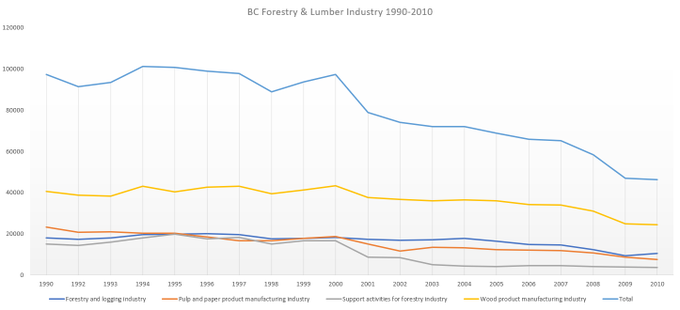

The retirement bump that was promised in 2000 didn’t materialize until right before the 2008 recession, so the cohort ready to move into those jobs didn’t get them as they were cut. But the seeds of the labour shortage were there. 2012 saw an outlier level retirement group. After that things cooled off for a few years, then in 2015 they started picking up steam again, and by 2018 statisticians could see that there was going to be a labour shortage. COVID19 layoffs obscured it for a while, but now that those layoffs are over we can see the result.

The labour shortage that was expected in 2000 didn’t happen, the one in ’06 was offset by the recession in ’08, and the delayed cohort of young people was more than enough to cover what should have been a shock to the system in ’12. But demographics keep marching on.

We’ve expected it 22 years, and now it’s here, and that’s a very good thing for young people (if inflation and housing prices don’t destroy the gains). Employers, look at those 3 things, if you don’t offer them, then your employees will get snatched up by an employer who does.