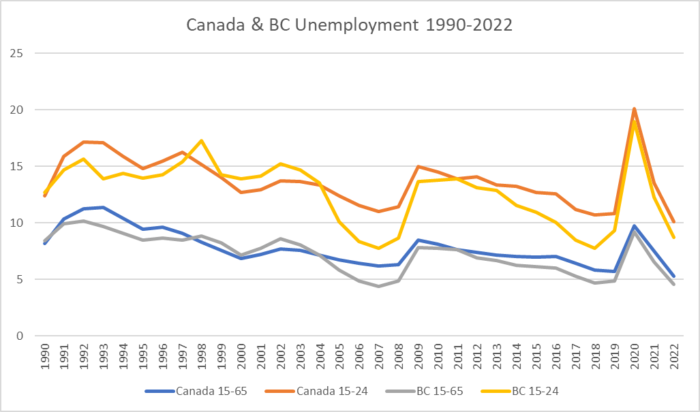

A reminder that I love StatsCan data (yes, I’m a nerd). Well I was looking at unemployment and labour market participation over the last decades (1990-2022) averaged yearly and broken out by 15-64 and 15-24 groups in both Canada as a whole and just BC. I was hoping to see if BC was an outlier anywhere and we really aren’t. But I found something else very interesting.

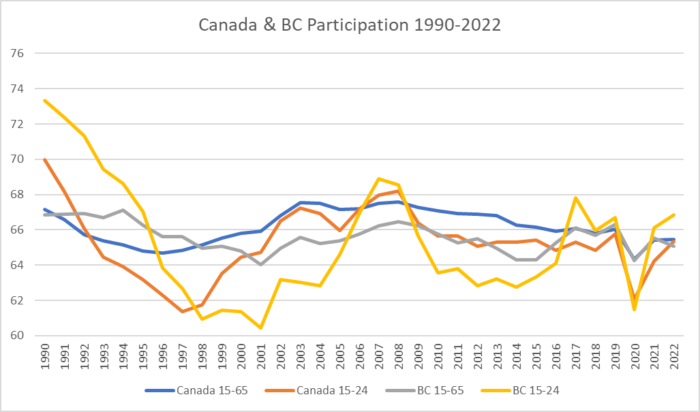

Three types of data tell us what’s going on: 1) unemployment rate (how many people in the workforce aren’t employed) 2) participation rate (how many people are in the workforce who could be) and 3) the difference between youth and all unemployment and participation.

This gives us info like knowing that generally high unemployment aligns well with low labour market participation because people will self-select out of the labour market when it’s bad. We also see the shift over the 90s as more people under 24 are in post-secondary showing a substantial decline in their labour market participation but not a massive raise in unemployment (because they’re not unemployed, they’re in university. This info also tells us that the unemployment rate changing for youth but not for the whole labour market is an impact that only hits youth.

So what happened during those 32 years? Well 1997-2004 was a bad time to be a youth looking for work. Youth labour market participation was going back up after the dip in the early 90s but the jobs weren’t there. Overall unemployment was fine, but if you were under 24 you were having a hard time. Then the strangeness that led me to writing this, 2005.

Suddenly youth unemployment across the country drops. It’s a small blip in Canada, but in BC it’s massive. Youth unemployment in BC goes from a high of 15% in 2002 to a slow drop to 13.5% in 2004, that’s normal. But in 2005 it’s 10% and by 2007 it’s at its lowest in the entire data set at 7.7%. It’s so sudden and impactful, and localized to only BC it must have some cause, but I don’t know what it is, and I was in that age range at the time. I remember a lot of help wanted signs, and I remember that for the first time in my adult life I could easily get a summer job or part time job.

This should have been fantastic, but the 2008 financial crash and oil price crash ended it. Unemployment for youth shoots right back up to 13% by 2009. The 2009 issue is clear, but what caused the drop in the first place? It was noticeable that youth in BC rejoined the labour market because of it. And it is very clearly a youth phenomenon because the dip for the all ages unemployment is minor.

Moving forward from that time though after the recovery from the financial crash the youth unemployment rate starts going down again, slowly this time, hitting 7.7 again in 2018, and then looking to stabilize in 2019 at 9%. I say stabilize because after the shock to the system from COVID it’s back to the 8-9% that seems to be a “normal” youth unemployment rate.

So what did I learn from the data? Youth participation lags youth unemployment slightly, but more perceptibly than all ages. Perhaps that means that youth are more likely to leave the workforce for school and other reasons if they can’t find work? Also, something happened at the end of 2004 or early 2005 to change youth employment in BC and it was impactful until the 2008 crash.

Finally I learned that the changes in the economy impact youth first and most. In every increase to total unemployment youth are impacted months before the general unemployment rate. The gap grows every time there’s a crisis and it always takes several months after the general unemployment goes down for the gap to begin shrinking.